1. Introduction

The hoof capsule is comprised of the hoof wall, sole,

frog, and bulbs of the heels, which, through the

unique continuous bond between its components,

form a casing on the ground surface of the limb that

affords protection to the soft tissue and osseous

structures enclosed within the capsule.

1 The hoof

wall is a viscoelastic structure that has the ability to

deform under load and then return to its original

shape when the weight is removed. It is well accepted

that abnormal weight distribution on the foot

or disproportionate forces placed on a section of the

hoof will, over time, cause it to assume an abnormal

shape.

1-4 These abnormal stresses within the foot

will also predispose the foot to injury or disease.

Increased stress or weight-bearing placed on a section

of the hoof capsule may originate from a single

source or it may be from multiple contributing factors

such as abnormal limb conformation, strike pattern,

amount of work, type of footing, and

inappropriate farrier practices. Excess stress

placed on one section of the hoof capsule can manifest

itself in a variety of ways, such as compressed

growth rings, flares or under-running of the hoof

wall, dorsal migration of the heels, and either focal

or diffuse displacement of the coronary band.6,7

Distortion of the hoof capsule of the forelimbs appears

to be related to limb alignment and load,

whereas deformation in the hind feet appears to be

different and related to propulsion. Because the

hoof capsule distortion of the forelimbs is commonly

associated with lameness and various disease processes,

only the forelimbs will be considered in this

report. Because the "normal" foot has never been

defined, each view will begin with what is perceived

to be an ideal, good, or healthy foot.

1,8 Palpation of

the hoof capsule often complements the visual examination,

and the areas where palpation is relevant

will be included. The goal of evaluating the

hoof capsule is to identify deformation and changes

in growth pattern that indicate abnormal distribution

of forces (stresses) on the foot. Because hoof

capsule distortion and abnormal loading usually accompany

lameness, farriery will form part of or

sometimes the entire treatment. Farriery is used

to help redistribute the load and help improve or

resolve the hoof capsule deformation.

2. Mechanism of Distortion

Evaluation of the hoof capsule morphology will indicate

where the hoof wall is unduly stressed; however,

the evaluation must be coupled with an

understanding of the abnormal distribution of forces

that lead to hoof capsule deformation. Understanding

the biomechanical forces leading to hoof

capsule distortions is also helpful for the clinician in

applying the appropriate farriery to modify these

stresses. There are many excellent reviews of basic biomechanics of the hoof in the veterinary literature.

1-5 Increased load or weight-bearing by a portion

of the wall has three consequences: (1) it may

cause deviation of the wall outward (flares) or inward

(under-running) from its normal position; (2) it

may cause the wall to move proximally; or (3) it may

decrease hoof wall growth. A reduction in load or

weight-bearing generally has the opposite effect.

Briefly, in the standing horse, the weight of the

horse borne by the limb is supported by the ground,

which opposes the weight with an equal and opposite

force. The force exerted on the foot by the

ground is termed the ground reaction force. The

term center of pressure (COP) is the point on the

ground surface of the foot through which the ground

reaction force acts on the foot. The center of pressure

varies among horses but is approximately located

in the center of the solar surface of the foot in

the standing horse. However, when the horse is

moving, the location of the COP changes dynamically.

The position of the COP at any point in the

stride determines the distribution of forces between

the medial and lateral and the dorsal palmar aspects

of the foot. When the center of pressure is

moved to one side of the foot, that side of the foot will

be subject to increased forces. If the COP is moved

in a palmar direction, the weight-bearing or load on

the palmar hoof wall is increased. Relating this to

hoof capsule distortions, if the COP is located more

medially, over time, a medial hoof wall flare (bending)

and a lateral under-running will develop. Or,

if the COP is located more dorsally because of increased

tension in the deep digital flexor tendon, the

hoof capsule will develop a higher heel with a flare

in the dorsal hoof wall. Farriery is used to change

the location of the center of pressure (to some extent)

and change the distribution of forces on the ground

surface of the foot.

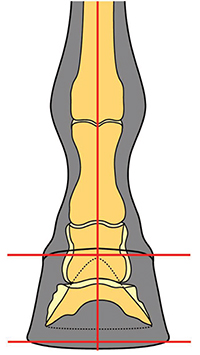

3. Limb Conformation

When evaluating hoof capsule deformation, limb

conformation should be considered. Abnormal limb

conformation affects the landing pattern and stance

phase of the stride. Few horses have ideal limb

conformation, and any change in conformation is

going to change the distribution of forces within the

hoof capsule, leading to deformation. In the frontal

plane, the forelimbs should be of equal length and

size and bear equal weight. A line dropped from

the scapulohumeral joint to the ground should bisect

the limb. Certain types of abnormal limb conformation

have been described.9 In the frontal plane,

abnormal conformation is described as valgus (the

limb's segment distal to the affected joint will deviate

laterally) or varus (the distal segment of the limb

will deviate medially). The joint most often affected

is the carpus, and, to a lesser degree, the

metacarpalphalangeal joint. Here, there will be excess

load placed on the hoof opposite the direction of

the deviation. If a line dropped from the metacarpalphalangeal

joint through the digit to the ground does not bisect the hoof capsule, the foot is considered

offset to one side (usually laterally) and therefore

increased load is placed on the opposite side of

the foot (Fig. 1).

|

|

Fig. 1. Distal phalanx within hoof capsule will be offset laterally.

Coronary band will be displaced proximally on media quarter/

heel. |

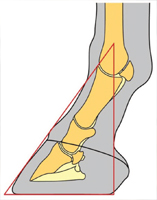

In the transverse plane, conformation

abnormalities are characterized by axial rotations

of the limb or its segments, either laterally or

medially. For example, a horse with a narrow

chest and a lateral axial rotation will land on the

lateral side of the hoof and then load the medial side

resulting in proximal displacement of the quarter

/heel on the medial side and causing the hoof deformation

termed "sheared heels"10,11 (Fig. 2). A limb

with a medial (inward) rotation of the digit relative

to the third metacarpal bone (toed-in) will develop a

hoof with a diagonal asymmetry, with a narrow lateral

toe and medial heel and a wide medial toe and lateral heel. The altered distribution of forces leading

to hoof capsule deformations follow a logical

pattern in which the overloaded sections of the hoof

are less developed and the under-loaded sections are

overdeveloped. In the sagittal plane, abnormal

conformation can best be described by the position of

the distal interphalangeal joint (DIP), either a flexural

|

|

Fig. 2. Horse with one heel bulb displaced proximally (sheared

heel conformation). Note the contour of the pastern above the

displaced heel bulb. |

deformity or marked dorsiflexion (ie, extension)

of the joint. The shape or conformation of the hoof

in the sagittal plane will be dependent on the tension

in the deep digital flexor tendon, the integrity of

the laminar apparatus, and the digital cushion-all

of which determine the angle of the solar margin of

the distal phalanx. A flexural deformity will overload

the toe, whereas marked dorsiflexion of the DIP

joint will overload the palmar section of the foot.

4. Evaluation of the Hoof Capsule

A detailed morphological examination of the foot

should begin with observing the horse in motion,

both going away from and toward the examiner, on

a firm, flat surface to note the landing pattern.

The foot is then viewed from all sides while it is on

the ground. Finally, the ground surface is examined

with the foot off the ground. Additionally,

small changes in the shape of the hoof capsule (such

as the coronet and the digital cushion) may be better

appreciated by careful palpation of the foot than by

visual inspection.

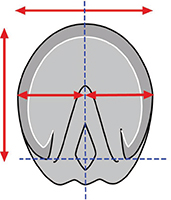

|

|

Fig. 3. Dorsal view: the hoof should be symmetrical. A line

drawn between any two comparable points on the coronary band

should be parallel to the ground. The hoof should be symmetrically

related to the distal limb such that a vertical line should

bisect the third metacarpal bone, the pastern, and the hoof (courtesy

of Dr Andy Parks). |

5. Dorsal Aspect

When the foot is viewed from the dorsal aspect, the

ideal hoof should be approximately symmetrical.

An imaginary line drawn between any two comparable

points on the coronary band should be parallel

to the ground. The medial wall should be the same

height as the lateral wall, but because it is often

slightly steeper, it may be slightly shorter. An

imaginary line that bisects the third metacarpal

should bisect a line drawn between any two comparable

points on the coronary band or the ground

surface of the hoof. Similarly, the hoof should be

symmetrically related to the distal limb such that an

imaginary line that bisects the third metacarpal

bone, bisects the pastern and the hoof, allowing for

the slight asymmetry caused by the different angles

of the medial and lateral wall (Fig. 3).1

When the

foot is viewed from the dorsal aspect, the shape of

the forefeet may be asymmetrical, with one hoof

being narrower than the other ("mis-matched feet").

Several abnormalities may be visible at the toe/

quarters such as flares or under-running of the wall.

The coronary band may be unevenly distributed,

most commonly by an uneven slope from one side of

the foot to the other. A distally directed arch in the

coronary band in the dorsal portion of the foot usually

indicates extensive remodeling of the distal phalanx

at the toe. Examination of the growth rings

below the coronet may show divergence of the rings

from one side to the other indicating uneven or excessive

load (Fig. 4). The angulation of the dorsal horn tubules toward the medial or lateral side of the

hoof capsule should be noted; normally they are

|

|

Fig. 4. Note divulgence of growth rings below the coronet from

the lateral to medial side. |

parallel, so when they appear tilted medially or laterally,

it suggests that the whole hoof capsule may

be tilted in that direction (Fig. 5). The position of

where the pastern bisects the hoof capsule should be

noted, that is, is its entry on the midline or displaced

medially or laterally?

On palpation, the coronary band of a healthy hoof

should feel thick and spongy. There should be no

evidence of a "ledge" or "trough" behind the proximal

margin of the hoof capsule when palpated. A depression

in the coronary band indicates that the

distal phalanx has displaced within the hoof capsule,

a finding that can be present in sound horses.12

This palpable depression will generally be accompanied

by a thin, flat sole, narrow frog, and contracted

heels. The dorsal aspect of the coronary band

should also be palpated for effusion of the DIP joint.

This is often seen with horses that have a broken

back hoof-pastern axis.

|

|

Fig. 5. Hoof with a separation in the dorsal hoof wall. Note the

angulation of the horn tubules toward the medial side of the

foot. Also note the focal "arch" in the coronet on the lateral side. |

6. Lateral Aspect

When viewed from the lateral aspect, the angle the

dorsal hoof wall forms with the ground is variable and typically related to the conformation of the digit.

The heel tubules of the hoof capsule should form an

angle with the weight bearing surface similar to the

angle of the horn tubules in the toe region. Tradition

has it that the angle of the wall at the heel

should match that of the dorsal hoof wall; however,

it is usually a few degrees less. As the foot accepts

weight, it expands and the ground surface at the

heels moves against the shoe, causing wear that

decreases the heel angle. The amount of wear is

dependent on the integrity of the structures in the

heel. The length of the dorsal hoof wall is similarly

variable but is determined by the amount of sole

depth present. There are two guidelines that relate

the proportion of the foot to the rest of the distal

limb.

|

|

Fig. 6. Conformation of the foot as it relates to the digit can be

depicted with a triangle. A line drawn down the dorsal surface

of the pastern and hoof is the hoof-pastern axis. A vertical line

that bisects the third metacarpal bone should intersect the

ground at the palmar aspect of the heels of the hoof capsule.

Connect these two lines with the angle of the dorsal hoof

wall and the ground surface of the foot to form a triangle (courtesy

of Dr Andy Parks). |

First, the foot-pastern axis describes the relationship

between the angles made by the dorsal

hoof wall and the dorsal aspect of the pastern with

the ground. Ideally, the dorsal hoof wall and the

pastern form the same angle with the ground so that the angle between them is 180° and the axis is

considered straight. Second, an imaginary line

that bisects the third metacarpal should intersect

the ground at the most palmar aspect of the ground

surface of the hoof. These two guidelines used in

conjunction with the angle of the dorsal hoof wall

and the ground surface of the foot combine to form a

triangle of proportions that represents the relationship

between the hoof and the distal limb regardless

of the size of the horse (Fig. 6).1

Evaluation of the

hoof capsule from the side view should begin with

the coronet as this structure can provide very useful

information. The healthy coronary band should

have a gentle, even slope from the toe to the heels,

and the hair should lie flat against the hoof capsule;

hair projecting horizontally may indicate excessive

forces on the associated hoof wall.

13 The coronary

band is dynamic, and its shape can be affected by

chronic overloading.

14 A proximally directed diffuse

arch at the quarters or a focal directed arch

toward the heels is evidence of chronic overloading

of that section of the foot (Fig. 7). A coronary band

with an acute angle at the heels relative to the

ground that bends distally at the heel to form a

"knob" appearance is an indication that the foot has

poorly developed or under-run heels and the hoof

wall at the heels has migrated dorsally (Fig. 8).

|

|

Fig. 7. A section of the coronet in the palmar section of the foot

has been displaced proximally (focal arch). Note the relationship

of the heel of the shoe and the origin of the defect, which

denotes excessive load. The foot on the right shows a change in

angulation of the horn tubules, curvature of the growth rings, and

a proximal displacement of the coronet (dorsal arch). |

|

|

Fig. 8. Foot with under-run heels showing the "knob" appearance.

Note the curve in the growth rings as the heels migrate

dorsally. There will often be a depression ("thumbprint") showing

the extent the heels of the hoof capsule have migrated forward

(arrow). Palmar view shows the decrease in structural mass of

the digital cushion. |

|

|

Fig. 9. Clubfoot. Note the coronary band has lost the slope and

is almost parallel with the ground. Also note the flare in the

dorsal hoof wall. |

A coronary band that is horizontal relative to the

ground and often accompanied by a flare in the

dorsal hoof wall would denote an upright or clubfoot

conformation (Fig. 9). Asymmetry of the height of the coronary band in the quarter/heel region on one

side occurs when the horse develops a "sheared

heel," a hoof capsule distortion resulting in proximal

displacement of one quarter/heel bulb relative to the

contralateral side of the foot.

15 The medial heel

bulb/quarter is more commonly displaced proximally,

as it is more common for the foot to be offset

laterally. The angle of the coronary band can be

used to estimate the position of the distal phalanx

within the hoof capsule. One study described the

angle of the coronary band of apparently normal

front feet to be 23.5° ± 3°.

16 If the angle of the

coronary band is >45°, the plane of the solar margin

of the distal phalanx will decrease. At the other

extreme, a coronary band parallel to the ground is

indicative of a high palmar angle, which is often

associated with a club foot or rotation of the distal

phalanx. The width of the growth rings below the

coronet should be equal from toe to heel. A disparity

in the width of the growth rings between the toe

and the heels is indicative of non-uniform circulation

of the coronary corium or excessive forces below

because wall growth is generally inversely related to

load. An example of this disparity would be chronic

laminitis typified by more horn growth at the heels than toe growth. However, regional irregularity in

spacing of growth rings is not uncommon; the most

frequently observed is a decrease in spacing at the

quarter associated with proximal displacement of

the coronary band as noted with sheared heels.10

The angulation of the horn tubules from dorsal to

palmar should be noted because horn tubules that

are parallel with the ground in the heel area are

associated with under-run heels. Flaring or concavity

of the dorsal hoof wall accompanied by underrunning

of the heels is readily appreciated from the

lateral side. The presence of hoof wall flares or

cracks are often caused by chronic, excessive overloading

of the hoof wall in the region in which these

defects are found.

10,11,14,17 Vertical cracks in the

quarter are more likely to occur with a sheared heel.

Horizontal cracks are usually the result of a disruption

of production of horn caused by coronary band

trauma or when a subsolar infection ruptures at the

coronary band.

7. Palmar Aspect

The heels are evaluated from the palmar aspect for

their overall width and height. The heels frequently

become narrowed when the foot itself is

narrow. Additionally, the central sulcus of the frog

may extend proximal to the hairline so that a cleft

becomes apparent in the skin of the pastern between

the heels. The overall height of the heels is readily

assessed from the lateral aspect, but viewing from

the palmar aspect is useful to compare the relative

heights of the two heels. For example, in the case

of the sheared heel, one heel is displaced proximally

in relation to the other. Another example is mismatched

feet in which there is a marked disparity in

heel height. The contour of the junction of the heel

bulbs with the skin can be evaluated relative to the

width of the hoof wall at the heels and the thickness

of the digital cushion (Fig. 10).

|

|

Fig. 10. A, Illustration shows various contours of the junction of

the heel bulbs with the skin; B, wide heel; C, contracted heel with

a poor digital cushion. Note also the sheared heel on this foot. |

8. Distal or Solar Aspect

When viewed from the distal surface, the ground

surface of the foot should be approximately as wide

as it is long. The foot should be approximately symmetrical about the long axis of the frog; the

lateral side of the sole frequently has a slightly

greater surface area that corresponds with the difference

in wall angles at the quarters described in

the dorsal view. The width of the frog should be

approximately 60% to 70% of its length. The

ground surface of the heels should not project dorsal

to the base of the frog. Imaginary lines drawn

across the most palmar weight-bearing surface of

the heels and across the heel bulbs at the coronary

band should be parallel and both lines should be

perpendicular to the axis of the frog (Fig. 11).

|

|

Fig. 11. The ground surface of the foot should be approximately

as wide as it is long (red lines) and approximately symmetric

about the long axis of the frog (blue lines). The heels should not

project dorsal to the frog (courtesy of Dr Andy Parks). |

1

If a three-dimensional object such as the foot

changes in one plane, it will change in at least one

other plane. Therefore, examination of the ground

surface of the foot reveals much about the changes

in the wall of the hoof capsule. For example, if the

contour of the wall is displaced away or toward the

median plane in the dorsal two thirds of the foot,

this usually corresponds with a flare or under-running

of the wall, respectively. If only one heel buttress

is displaced dorsally in relation to the base of the frog, it usually corresponds with the proximal

displacement of that heel plus or minus the quarter

termed sheared heel.

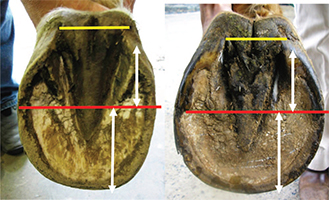

The author begins the evaluation of the solar surface

of the hoof capsule by drawing a line across the

widest part of the foot. This line forms a consistent

landmark and is located just dorsal to the center of

rotation (of the distal interphalangeal joint). With

the use of this line as a starting point, there should

be approximate proportions from this line to the

perimeter of the toe and to the base of the frog (Fig.

12).

|

|

Fig. 12. Two examples of a line drawn across the middle or

widest part of the foot to determine proportionality (red line) by

use of the base of the frog (yellow line) and the perimeter of the

toe. White lines are the distance from the middle of the foot to

the end of the heel and to the toe, respectively. Note that both

heels have migrated dorsally and both frogs are receded below the

hoof wall. |

This creates a relative proportion from the

front of the foot to the palmar aspect that is related

to the alignment of the center of rotation in the

middle of the foot or, when shod, the middle of the

shoe. The normal solar surface of the foot may be

wider laterally than medially. The width of a

healthy frog should equal 60% to 70% of its length;

therefore, the width and length of the frog should be

critically evaluated using these guidelines.

1,8,18 The

untrimmed frog should be on the same plane with the

hoof wall at the heels; it should not be receded between

the hoof wall or protrude beyond the solar surface of

the hoof wall. In general, the frog is usually constant

in length, and its axis is almost always aligned with

the medial plane of the foot but its width is variable.

As the frog functions as an expansion joint, a decrease

in width is generally associated with contracture of

the hoof capsule at the heels. The frog of a healthy

hoof has sufficient depth at its dorsal aspect to reach

the bearing surface.

17 The relationship of the untrimmed

frog to the sole indicates the position of the

distal phalanx within the hoof capsule (ie, the angle of

the solar margin of the distal phalanx).

18 For instance,

if the apex of the frog is deeply recessed and the frog

appears to be angling toward the coronary band at the

toe, the distal phalanx is probably similarly positioned,

creating a negative palmar angle. The position of the heels of the hoof wall relative to the base of the

frog should be evaluated. Ideally, the most palmar

extent of the bearing surface of the heel tubules

would be at the base of the frog and very near a

vertical line drawn thru the middle of the third

metacarpal bone. When the ground surface of the

heels is dorsal to the base of the frog, the heels are

low, under-run and/or increased in length. The

structures of the heel (hoof wall, buttress, angle of

sole, bars) should be present and well-defined.

If the heels have migrated dorsally relative to the

frog and the structures are present, the heels are

considered low; if the structures of the heel are absent

or damaged, then the heels are considered under-

run. The bars of the heel should be straight as

curvature indicates contracted heels. The proportionality

of the foot dorsal to the widest part of the

foot should be evaluated. As the heels move forward,

|

|

Fig. 13. A rasp is placed across the foot and a ruler is placed

within the collateral groove of the frog to measure the distance

between the deepest part of the groove and the plane of the solar

surface of the foot. This simple technique can be used to approximate

the sole depth (courtesy of Dr John Schumacher). |

there will generally be a substantial increase

in the proportion of the toe relative to the heels.

A long toe will also be accompanied by an increased

distance between the toe and the apex of the frog.

The sole-wall junction should be solid and compact.

Widening or fissures in the sole-wall junction and

hoof wall separations dorsal to the sole wall junction

occur with lengthening of the toe. The healthy sole

tends to be concave and callused adjacent to the sole

wall junction (white line). It should have a gradual

slope from the apex of the frog to the sole wall

junction and not a significant "trough." The sole

should be between 10 to 15 mm thick beneath the

margin of the distal phalanx and should not deform

when hoof testers are applied. A ruler calibrated in

millimeters can be placed within the collateral

groove of the frog to measure the distance between

the deepest part of the groove and the plane of the

solar surface of the foot. The consistent distance

(10 to 11 mm) between the distal phalanx and the

collateral groove depth at the apex of the frog allows

the clinician to predict sole depth. If one imagines

moving the ground plane proximally so that the

distance from the ground plane to the depth of the

collateral groove decreases, it becomes clear that

sole depth decreases as collateral groove depth decreases

13

(Fig. 13).

Horses with poor heel structure typically have a

poorly developed digital cushion and thin collateral

cartilages. These soft tissue structures determine

the overall conformation of the palmar portion of the

foot. Clinicians should gain an appreciation for

variation in the consistency and overall size of the

digital cushion and collateral cartilages. The digital

cushion can be palpated between a thumb placed

between collateral cartilages and the fingertips

placed on base of the frog. A sense of "normal" can

be acquired by palpating the digital cushions of

sound horses with "good feet" and comparing those

findings with those of horses with poorly conformed

feet. The depth of the combined tissues of normal

digital cushion and frog should be approximately 2

inches, but this can vary among different breeds.13 Horses with under-developed digital cushions typically

have low or under-run heels that lack stability

and can be easily distracted independently or they

may have contracted heels and narrow, non-weightbearing

frogs.19,20

9. Conclusions

The clinical examination of the equine foot has been

well-described and is generally performed in lameness

cases. Evaluation of the hoof capsule during

the lameness examination will provide additional

information as to the etiology and treatment of the

lameness but will also serve as a guideline to apply

therapeutic farriery and other preventive measures

to maintain a healthy hoof. The morphology of the

hoof capsule reveals deformation and changes in

growth that occurs after increased or reduced force.

The relationship between the limb and the foot indicate

conformations that predisposes the foot to

abnormal weight-bearing. Inversely, with the use

of abnormal distribution of forces and the subsequent

hoof capsule distortion as a template, appropriate

farriery or therapeutic farriery will form at

least part of the treatment plan. Here it is essential

to be familiar with the biomechanics of the foot

and how these forces can be altered to change the

distribution of forces or the focal stresses on a given

section of the foot.

References

- Parks AH. Form and function of the equine digit. Vet Clin N Am Equine 2003;19:285-307.

- Parks AH. Aspects of functional anatomy of the distal limb, in Proceedings. Am Assoc Equine Pract 2012;58:132-137.

- Johnston C, Back W. Hoof ground interaction: when biomechanical stimuli challenge the tissues of the distal limb. Equine Vet J 2006;38:634-641.

- Eliashar E. An evidence based assessment of the biomechanical effects of the common shoeing and farriery techniques. Vet Clin N Am Equine 2007;23:425-442.

- Parks AH. Therapeutic trimming and shoeing. In: Baxter GM, editor. Adams & Stashak's Lameness in Horses. 6th edition. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell; 2011:986-992.

- Turner TA. The use of hoof measurements for the objective assessment of hoof balance, in Proceedings. Am Assoc Equine Pract 1992;38:389-395.

- Redden RF. Hoof capsule distortion: understanding the mechanisms as a basis for rational management. Vet Clin N Am Equine 2003;19:443-462.

- O'Grady SE, Poupard DA. Physiologic horseshoeing: an overview. Equine Vet Edu 2001;13:330-334.

- Castelijns HH. The basics of farriery as a prelude to therapeutic farriery. Vet Clin N Am Equine 2012;28:316-320.

- O'Grady SE, Castelijns, HH. Sheared heels and the correlation to spontaneous quarter cracks. Equine Vet Edu 2011; 23:262-269.

- O'Grady SE. How to manage sheared heels, in Proceedings. Am Assoc Equine Pract 2005;51:451-456.

- Turner TA. Examination of the equine foot. Vet Clin N Am Equine 2003;19:309-332.

- Schumacher J, Taylor D, Schramme MC, et al. Localization of pain in the equine foot emphasizing the physical examination and analgesic techniques, in Proceedings. Am Assoc Equine Pract 2012;58:138-155.

- Turner TA. Predictive value of diagnostic tests for navicular pain, in Proceedings. Am Assoc Equine Pract 1996;42:201-204.

- Dabareiner RM, Moyer WA, Carter GK. Trauma to the sole and wall In: Ross MW, editor. Diagnosis and Management of Lameness in the Horse. 2nd edition. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2011:309-319.

- Eliashar E, McGuigan MP, Wilson AM. Relationship of foot conformation and force applied to the navicular bone of sound horses at the trot. Equine Vet J 2004;36:431-435.

- Booth L, White D. Pathological conditions of the external hoof capsule In: Floyd AE, Mansmann RA, editors. Equine Podiatry. St Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:224-252.

- Dabareiner RM, Carter GK. Diagnosis, treatment and farriery for horses with chronic heel pain. Vet Clin N Am Equine 2003;19:417-441.

- Bowker RM. The concept of the good foot: its evolution and significance in a clinical setting. In: Ramey P, editor. Care and Rehabilitation of the Equine Foot. Lakemont, Georgia: Hoof Rehabilitation Publishing LLC; 2011:2-34.

- Moyer WA, Carter GK. Examination of the equine foot. In: Floyd AE, Mansmann RA, editors. Equine Podiatry. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2007:112-127.